This and other photographs with this article were taken on 13th May 1973.

This and other photographs with this article were taken on 13th May 1973.

I've always considered myself incredibly lucky as a youngster to have come under the tutelage of Jim Cunningham, an experienced caver and Wanderers member at the time.

Bridge Hall, Bar Pot. John Cordingley holding ladders, Graham Proudlove with flash. Photographer: Jim Cunningham

Graham Proudlove and I were at school together where Jim was a physics teacher. We'd read a couple of caving books borrowed from the local library and decided that a life of adventure underground was for us. Our geography teacher, David Pack (a man of the finest calibre on whom I could write a book!) organised youth hostelling visits to the Dales and Jim was one of the staff who used to give up his free time to help out. We stayed at Kettlewell on one of these trips and a walk we did involved going from Arncliffe over Old Cote Moor. High on the fell David Pack stopped at a shakehole and said “Something for you here Jim”. I think that was the moment Graham and I realised he was a caver and, from that point onwards, we gave Jim no peace!

We pestered and pestered him to take us caving and in the end he said “OK, come to the physics lab at lunchtime and we'll have a talk about it” He showed us a couple of Oldham lamps and said we could borrow them and go to Dow Cave – if we could persuade our parents to get us there. He provided us with a survey; it had a big red cross on the start of Dowbergill Passage and one on the Hobson's Choice choke, with strict instructions to go no further. He must have reckoned that we'd no chance of getting our parents to co-operate but somehow they were cajoled and off we went. On that day early in 1971, Graham was thirteen and I was fourteen.

It seems incredible now that such a situation occurred. But looking back on it I think Jim must have realised we were actually quite well prepared. We'd studied Don Robinson's “Know The Game Potholing” booklet and put together the recommended emergency kits (“lights, spare lights and spares for all lights”, high energy food, etc). We each had a boiler suit and “waistlength” of thin rope and, with helmets and proper caving lamps, I remember feeling quite confident of making the trip safely. We were extremely careful underground and, having had to work out everything for ourselves, we gained a great deal from the adventure. Most important of all we learned self sufficiency, an extremely valuable lesson which still brings benefits on caving trips to this day. We'd been completely in control of our own destiny in Dow Cave and it had been exhilarating.

The second trip was to Calf Holes; Jim was with us this time; he must have reckoned that the entrance pitch was perhaps better done supervised! Graham had acquired a genuine “Texolex” helmet by this stage and I remember being green with envy! It all went very well and eventually it was decided that it was time for us to have a go at a more serious pothole. Some time later, there we were with Jim and a huge heap of ropes and ladders, perched on the ledge where the old ring bolts used to be above the main part of the pitch in the entrance shaft of Rowten Pot. The situation was quite frightening with this great black pit next to us, from which came the ominous roaring of water far below. We watched Jim connecting six ladders onto each other and lowering them down into the terrifying depths. A huge length of lifeline was unchained, stacked neatly – and then the end was passed to me to tie onto.

Base of Bar Pot's big pitch. Graham Proudlove by ladder, John Cordingley holding flash. Photographer: Jim Cunningham

Base of Bar Pot's big pitch. Graham Proudlove by ladder, John Cordingley holding flash. Photographer: Jim Cunningham

It was quite a moment when I stepped over the edge to begin the rhythmic descent, rung by rung (using the climbing method advised in Robinson's booklet). I felt very alone and remember thinking “This is it; this is the real thing at last!”. It was quite frightening but also hugely exciting. The tackle had been obtained from the Wanderers' HQ at Braida Garth. All the best ladders were down Pippikin (as the club's finest discovery was still being explored). The ones we had in Rowten were very much third issue, with slipped ferrules causing wonky rungs and variable spacing leading to a rather less than graceful climbing style. Eventually I could no longer feel any more rungs under my feet; I was at the bottom of the ladder.

I looked around for the best place to step onto the floor but saw, to my horror, that the base of the pitch was still too far away to get off. I glanced back up at 150 feet of slender wire ladder whilst buffeted by the icy spray and instantly knew there was only one way out of this predicament. I gave two good blasts on the whistle, felt the lifeline tighten reassuringly and started back up the long pitch.

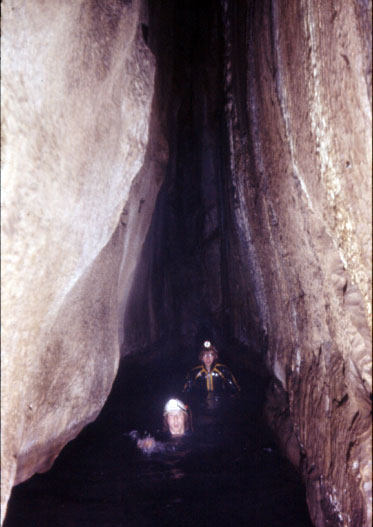

John Cordingley with Graham Proudlove behind, in the deep water at Pool Traverse Gaping Gill, Photographer: Jim Cunningham

It was one very exhausted young teenager which finally flopped back onto that ledge to join the others, soaked through and with arms burning from the physical effort. Jim added an extra ladder and then calmly said; OK John, off you go” whilst holding out the end of the lifeline. Surely he'd have asked one of the others to go down next so I could recover a bit, I thought? But no, he wanted me to go back down right away! He cracked a joke about cavers wearing kneepads to make it more comfortable whilst praying for strength at the bottom of big pitches and the next thing I knew I was back in that vast shaft with the rungs going up past my face once again. Sometimes, if you want to be a caver, there are times when you have to draw on reserves of energy far more than you'd ever have to in normal life. I learned a lot about that on the big pitch of Rowten Pot that day. Nowadays a teacher wouldn't dream of encouraging a pupil to do some of the scary things we got up to but Jim was a very good judge of a person's capabilities and he never let us do anything really foolhardy. Looking back on those days now, after a lifetime of cave exploration, I don't think we could have had a better start.

There was quite a strong Scout movement where we lived; Graham and I were both members and we soon cottoned on to the existence of the “Speleologist” badge. It was one of the hardest badges to get and I don't think any other Scout in the town had achieved this. Among other things we had to keep a caving diary and survey a cave. We chose Upper Long Churn and produced a large scale drawing after borrowing some of my dad's draughtsman's equipment.

John Cordingley outside the entrance to Bar Pot, with Jim Cunningham walking out of shot.

Photographer: Graham Proudlove

You couldn't even start work for this badge unless an experienced caver had agreed to act as a mentor. Of course it was Jim who performed this role and I've still got my badge, together with the certificate which came with it, signed by Jim himself. And to be perfectly honest, I'm still rather proud of it!

Jim accompanied Graham and me down Bar Pot some time later, to get our first view of the awesome Main Chamber. This trip went without real incident and almost seemed routine. But I had a cheap camera with me and some second hand bulb flashguns. Jim was an excellent cave photographer of course and he showed us how to use the equipment underground. He took some of the shots himself, so Graham and I are in them (see the images with this article). By this stage we were both keen to tackle harder trips and Jim must have realised that the time had come to encourage us to join a caving club – but not the Wanderers as he thought it “might not be suitable”. (I suspect he realised we were likely to involve ourselves in outrageous drunken antics which could backfire and ruin his teaching career!) So we fell in with our local Lancashire Caving & Climbing Club (of which both Graham and I have very fond memories, particularly of a certain Les Mottram). Time moved on and we drifted over to the Craven Pothole Club, both of us having to wait till our 16th birthdays before we could actually join. That was the start of our regular weekend caving and the rest, as they say, is history.

As time went by Graham and I did a lot underground together but eventually we developed our own specialised interests within caving. He became fascinated by cave biology and went on to write the definitive text book on cave fishes of the world. I took up cave diving and developed a love of emptying line reels down unexplored passages. Both of us are still actively caving and I've often wondered whether Jim Cunningham had any idea what he'd started in the physics lab that lunchtime, when he presented us with the two Oldham lamps all those years ago. Thanks Jim!

John Cordingley